|

The Jameson Family Photo Gallery |

1

DANIEL JAMISON OF LIME RIDGE:

HIS DESCENT AND DESCENDANTS

Prepared for

Richard A. Jameson

By W. M. Baillie

2007

CONTENTS

Chap. 1 Immigrant Dr. David Jameson 3

Chap. 2 Dr. James Jameson of Allentown 17

Chap. 3 Daniel Jamison of Lime Ridge 23

Chap. 4 Jamisons in the Civil War 35

Chap. 5 Benjamin F. Jamison 44

Index 47

Copyright © 2007 by Richard A. Jameson

All rights reserved, including reproduction in any electronic form.

Chapter 1

IMMIGRANT DR. DAVID JAMESON

The lineage of Daniel Jameson (born 1812) of Lime Ridge, Columbia County, Pennsylvania goes back to a Scottish immigrant, Dr. David Jameson (born ca. 1715), an Edinburgh-trained physician who came to America in the 1740s and lived at York, PA. The line descends through David’s son James (b. 1771), also a physician, at Allentown, PA, and then to James’s son Daniel. The immigrant David Jameson achieved distinction as a physician, a colonial and revolutionary militia officer, and a judge at York. Although a relative newcomer to America, David Jameson was an early, enthusiastic and heroic advocate of the colonies’ independence from Great Britain. Three of David’s sons also became well-known physicians: Thomas (at York), James at Allentown, and Horatio Gates (b. 1778) at Baltimore, where he pioneered surgical techniques, authored a landmark home-medicine text, and founded a medical college. Horatio also wrote a brief biographical sketch of his father which was published from his manuscript in 1887: Memoir of David Jameson, Esq., M.D., Lt. Colonel of the Provincial Forces and Colonel of the Revolutionary Forces of Pennsylvania. The Memoir is the basis for much of what follows, amply supplemented by surviving letters and journals.

The Jameson family is featured in the “York History” website of the York Daily Record:

Famous family gets early fame

c. 1745, Future York County

Dr. David Jameson, a 30-year-old physician, opens a medical practice in York. But the call of war draws him into service. He sustains serious wounds in the French and Indian War, and the 61-year-old marches with county troops in the Revolutionary War.

His son, Horatio Gates Jameson, eclipses his father in fame as a physician. He studies medicine under his father, practices medicine at age 17 in Somerset County, and moves to Baltimore, where he earns a medical degree at age 35. He founded Washington Medical School in his new home and published accounts of several unusual and pioneering operations in the early 19th century.

John Gibson, Horatio Jameson's grandson, eclipses his forebear in local prominence. Gibson served as county judge in the 1880s and compiled an extensive county history in use today.

A. Dr. David Jameson, Scottish Immigrant

Memoirist Horatio Gates Jameson records a family tradition that his father David Jameson was of the Campbell clan in Scotland and a cousin or nephew of the Duke of Argyle (Archibald, 3rd Duke, died in April, 1761). In the main section (“SKETCH”) of his Memoir the biographer assumes the truth of the tradition and regularly names his subject “Argyle,” trading on the cachet of a noble linkage in the family line. Horatio’s daughter Cassandra Jameson Gibson wrote, “I remem-ber hearing it said that he was a cousin of the Duke of Argyll, and that on coming to this country the Duke presented him with a gold-headed cane.” So far, however, no evidence has turned up about David Jameson’s parentage in Scotland. We can assume, at least, that he was of a well-to-do family which had the connections and wherewithal to send him through medical school.

The Memoir also asserts that David Jameson was a native of Edinburgh, “the cradle of his infancy,” and that he must have been of age 25, at least, when he came to America; however, the doctor’s birth year and place have not been established. (Jameson’s family Bible, unfortunately, does not survive; it reportedly passed to his daughter Jane in Columbus, Ohio, and it was left “in a lumber-room” and “was exposed to the weather and destroyed.” ) The biographer seems on firmer ground when he asserts that Jameson was a graduate of the Medical School of Edinburgh University, for David Jameson certainly had a successful medical career in America.

According to family tradition, after earning his medical credentials at Edinburgh Jameson came to America in the 1740s, landing at Charleston, SC. Various sources assert that he came over in 1740, but he is also said to have sailed in company with his good friend Dr. Hugh Mercer (later a General in the Revolutionary War who was killed in the battle of Princeton)—but Mercer fought with the forces of Bonny Prince Charles at Culloden Moor on 16 April 1746 and, like many other Scotsmen who survived that disastrous battle, came across the Atlantic in the spring of 1747. It is probably safe to say that David Jameson emigrated “in the 1740s.”

At that time, Charleston in South Carolina was a cultured city with perhaps the most fashionable and high-toned elite class of any American town. Dr. Jameson was welcomed into that society, and his son narrates an incident there “about which we have often heard him speak.” At the ball-rooms David soon was taking up with a young woman of fashion. As it happened she had been receiving the ardent wooing of a young Charleston gentleman, and this young man became extremely jealous of her attentions to Jameson. Favoring the Scotsman, she so managed affairs that he, rather than the Charleston beau, was her escort to an important ball. The thwarted suitor resolved to take his revenge by killing the upstart intruder. In this era, gentlemen routinely wore swords to formal functions, and he pulled his sword from its scabbard and, while Jameson was dancing with the girl, swirled the sword between the Scot’s legs, nearly tripping him. Jameson thought it might have been accidental, but then the rude affront was repeated, and still he continued to dance.

When the dance ended and the dancers were seated, Jameson told his companion what had happened and asked if there were some “understanding” between her and the beau. She told him about the rival’s ardent wooing, but insisted that she had not led the man on nor given him any encouragement. Jameson declared that he would “seek satisfaction” of the swordsman by a challenge the next day; he was greatly surprised and pleased when the spirited young lady exclaimed “Amen!” She herself, she explained, was of Scottish descent and had learned from her father that “the man of honor will do no wrong, nor less suffer wrong.” They continued to enjoy the dance as if nothing had occurred. When their group was leaving, however, someone suddenly seized Jameson, pulled him into a dark room, and locked the door. The party members were startled, but after a few moments some men forced the door open and discovered Jameson in the dark with drawn sword, fending off the attack of the rival. The incident ended without bloodshed, and the rival was so shamed that he was forced to leave the city. After a few months David Jameson himself left Charleston and traveled North; he and the young lady had an “understanding” of future marriage, but she succumbed to a fatal fever.

This romantic incident, narrated with gusto by the Memoirist, provides some idea of David Jameson’s character.

After Dr. Jameson left Charleston for the North, he may have settled first at Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, but by the year 1755 he was a resident of the town of York in south-central Pennsylvania. His medical practice flourished, and he drew patients from a wide expanse around the city. He is listed in tax assessment lists at York Town in various years 1764 through 1782 and is sometimes identified as a physician or surgeon (1779, “Jameson, David, surgeon”); the records do not show his address in the town. His son James was born there in 1771 and probably his son Horatio Gates in 1778 (and probably other children as well).

By 1768 David Jameson took up parts of three warrant tracts about 1½ miles south of York Town, in all about 130 acres on rivulets flowing into Codorus Creek. There he established a country seat which was famed for its beauty, both of the mansion-house and the landscape. His great-grandson, editor of the Memoir, described it as a

spacious domain near the ancient borough of York, which, with a refined and cultivated taste, he adorned and beautified, . . . adding to its natural beauty, all that art could devise to make it fair to view, and where he dispensed a generous and kindly hospitality.

The estate comprised two warrant tracts which were surveyed 24th and 25th October 1768. Although another man, John Coates, patented the tracts (to obtain ownership from the Commonwealth), Jameson obtained the title.

Late in life Jameson moved his family westward to the newer town of Shippensburg and sold away his York Township estate: on 2 January 1796 David Jameson, described in the deed as a “practitioner in physick” at Shippensburg, and his wife Elizabeth sold 129 acres for £340 to two men, Ralph Bowie and Jacob Barnitz. The next month Barnitz sold his moiety or half-right to his partner, and a month later the property was advertised for lease in the York Recorder, Herald and Advertiser:

TO BE LET,

And possession given immediately, a Farm within about a mile and a half of York Borough, lately owned by Dr. Jameson. For terms apply to the subscriber in the Borough of York. RALPH BOWIE

March 29, 1796

Jameson’s famed mansion-house burned down in 1855. While at York he had also obtained in 1774 by order of the Land Office fourteen acres adjacent to the estate, land which was described by the surveyor as “Poor and Stoney some pretty good wood on it but not any water.” He sold this wood lot 10 October 1774 for £16.

Apart from this farm south of York, David Jameson, like most well-to-do Americans at the time, bought and sold lands regularly. He was one of many men on a list of “Applications for lotts in York 1764 26th Sept.”; he applied for three vacant lots adjoining the three lots of the Moravians (on which they established a church and cemetery). On 24 February 1785 he obtained a warrant to take up 400 acres in Northumberland County, but this right was released without survey.

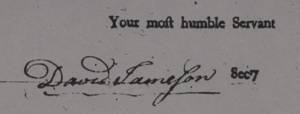

After the French and Indian War Dr. Jameson served as the Secretary of a group of Pennsylvania officers who banded together, in the words of his printed form-letter, to

join in an Application by Petition to the GOVERNOR, for Liberty to take up, upon the common Terms of paying Purchase-Money and Quit-Rent, a large Quantity of Land for a Settlement on the Branches of the Susquehanna [in the New Purchase lands of 1768].

The officers turned down the Governor’s offer for a joint grant of 50,000 acres, asking instead for individual grants. Various officers received large tracts in the New Purchase before other applications were accepted, but David Jameson, the prime mover in their effort, doesn’t seem to have been among these fortunate warrantees. The group’s application became very controversial in the Colony, a problem anticipated in Jameson’s letter, which cautions the recipients:

It is thought adviseable by the Committee to recommend to all the Officers a Caution against disclosing this Matter, either by writing Letters, or speaking of it.

The document closes with Jameson’s signature:

Jameson was also one of a group of Pennsylvania officers who tried unsuccessfully to obtain grants from the Crown of lands in Virginia, sending representatives to Williamsburg in 1764 and as late as 1783.

Jameson did take up three warrant tracts in western Pennsylvania near the Allegheny River, land which he probably had seen during his militia service; in 1774 he patented these tracts, in total over 1000 acres.

B. David Jameson at War

York County in the mid-Eighteenth century was still a frontier region and was repeatedly under alarm of raiding Indians, particularly during the French and Indian War (1756-1763). Skirmishes between British and French/Indian units on the Pennsylvania frontier in 1754 and 1755 led up to British General Braddock’s disastrous expedition against Fort Duquesne (at modern Pittsburgh). These were the opening battles of what became the first world-wide war, known in Europe and Asia as the Seven Years War.

During this conflict Dr. David Jameson, already a leading citizen of York, took an active leadership role in the Pennsylvania colonial militia. He rose in rank from ensign to lieutenant-colonel, was stationed at several frontier forts, and was engaged in several battles.

Early in the War he was severely wounded and left for dead; the story is narrated at length by his son in the Memoir. At the time Captain Jameson was stationed with a small troop at Fort Littleton, a small stockade along the path from Carlisle westward to Pittsburgh. Early in April 1756 he took nineteen men from the fort to join a militia force in pursuit of a troop of Indians who had raided a frontier settlement, killing many and dragging off several captives. Jameson took along his pet dog and also an Indian porter named Isaac. Trailing the raiders, the troop of about fifty militiamen was met by a slightly larger force of Indians near Sideling Hill. For two hours they traded rifle volleys—the militia loaded and fired 24 times—and the losses were high, with each side losing about twenty men killed and as many wounded. Near the end of the battle, Jameson was shot in the chest; the ball entered below his left nipple and went straight through and out at the shoulder blade. His few remaining soldiers left their unconscious ensign on the field for dead. Fortunately, they laid him in a bed of leaves behind a log, and the returning Indians, bent on taking scalps, failed to see him.

Isaac left the scene among the fortunate survivors, and took David’s dog with him. [He also took away “the scalp of Captain Jacobs,” one of the opposing chiefs.] When they stopped to prepare the evening meal, Isaac tied the dog’s leash to a bush, and was dismayed when “Rover” broke the branch and dashed away down the path on which they had come. Four or five hours after the battle, Jameson revived and found his faithful dog lying beside him, licking blood from his wound. Jameson, desperately thirsty, crawled to a nearby spring and drank his fill. The cold water helped to stanch his bleeding also. He tore strips from his clothing and bandaged his wounds as well as he could.

Though barely able to stand, he staggered off to return to the fort; before he had gone far, he lay down exhausted, without a covering. The next morning he found himself completely covered with snow except for a small hole above his nostrils. Two days after the battle, after heroic effort he managed to get back to Fort Littleton. When the sentry shouted a challenge, however, his lungs were so weak that he was unable to answer, and the guard immediately shot at him; fortunately the exhausted captain was collapsing, having reached his goal, and the shot went over his head. A patrol came out of the fort and the men were astonished to find their captain alive, with his faithful dog standing beside him.

The preceding day, Captain Hans Hamilton had written hastily to his superior to inform him of “the Melancoly News that Occurd on the 2d Instant” when after the skirmish “only 5 of our men returnd, and mostly wounded.” He reported that

Capn Culbertson & Docr Jameson is thought to be Kild, having recd several wounds. I have sent a letter to Capn Potter, Desiring him to Come & Assist us to bury the Dead, & forward an Express for Doctr Prentice [to come tend to the wounded].

Jameson was sent to Philadelphia for medical care, and after some months returned to duty; he suffered ill effects from the wound, however, to the end of his life.

On 19 April 1756, Dr. Jameson was commissioned a captain in the Third Battalion which built and garrisoned Fort Augusta at the Forks of the Susquehanna. For a time in 1756-1757 he was in charge of Fort Halifax, an outpost downriver from Fort Augusta. The Pennsylvania Archives preserve his brief summary of that fort’s supplies:

__________________________________________________________________________

GARRISON. PROVISION. AMMUNITION.

2 Sergeants 14000lb. Fresh beef 160 lb Gun Powder

2 Corporals 1 Barrel Salt 300 lb Musket Ball

42 Private Men 700lb Flower [flour] 60 lb Shot and lead.

DAVID JAMESON.

Octobr ye 9th, 1756.

[Endorsement on the back:] Augusta Regiment, Return of Men, Provisions, Ammunition, Capta. Jammeson at Fort Halifax, 9 8ber, 1856 [i.e., 1756]

_____________________________________________________________________________

Earlier, on 4 December 1756, Captain Jameson wrote in confidence from Fort Augusta to William Allen at Philadelphia; Allen was Chief Justice of Pennsylvania and the richest man in the colony. In this extraordinary letter Jameson described severe problems in his regiment at the frontier fort and complained explicitly about his commanding officer, Colonel William Clapham:

Honored Sir:—The great concern I am under for the irregularities in our regiment, and the sincere desire I have for the provincial service to go on well, have caused me to break through the diffidence under which I have labored for some time, as to representing the bad state of our regiment, and complaining of the injuries I have received from Col. Clapham. The character you bear of exerting yourself for the public good has induced me to exhibit them first to you, for your consideration; in the hope that, if they appear to you likely to obstruct the service of his Majesty or the Province, you will deliver the enclosed complaint to his honor, Governor Denny, and at the same time make mention of those things I write concerning the regiment: if you think otherwise, then I beg you to excuse my presumption, for I act from a mistaken notion of my duty.

The men of the regiment are not yhet trained, and therefore of no more service to the Province than a number of men, gathered together in a hurry, would be.

The Col. often damning the service, pointing out the disadvantages of serving in this Province, and threatening to leave it and go to the Indian country, whereby many officers and men are prejudiced.

He goes on to list other specific grievances: “officers frequently arrested” and held without proper court martial, a license for selling dry goods given to one extortionate trader, officers verbally abused, etc. After listing these problems, Jameson closes with an acknowledgment that his letter violates normal military protocol:

I know not but what I have done may be looked upon as ill, because Col. Clapham is my commanding officer. You may depend that all, or at least the most of what I assert, can be sufficiently proved. Now, sir, I submit to your wise judgment, whether the complaint and the things mentioned in this letter ought to be made known to the Governor.

Perhaps partly as a result of this letter, Col. Clapham was replaced as commander of Fort Augusta within a few months. Jameson seems to have suffered no ill effects from his unusual “venture” in insubordination.

In fact, the opposite was the case: he rose rapidly through the ranks. His son says (Memoir, p. 22) that he was promoted rapidly “to the rank of Captain, without an intermediate lieutenancy.” A staff report by his commander, Colonel Burd, in 1757 included this evaluation:

Captain Jameson, a gentleman of education; does his duty well, and is an exceeding good officer.

On 24 April 1759 he was brevetted as Major of the Second Battalion, and a year later was listed as a Brigade Major in the First Battalion. He was involved in enlisting recruits, in lending money to soldiers, and in purchasing provisions for the troops. Surviving letters show that his duties took him to widely-scattered posts, including Forts Augusta and Halifax on the Susquehanna and Forts Pitt and Ligonier further west. One such letter, addressed to militia leader Edward Shippen at Carlisle, from Fort Halifax, warns of an impending raid by a large body of Delawares:

Oct. 13th, 1756

Sr: As Coll. Clapham is at Carlisle, and it being reported hear that his Honour, our Governor, has gone round by York, and therefore not knowing when he will receive an Express that is sent to him from Shamokin, I have thought fitt to send an abstract of Maj. Burd’s Letter to me that arrived hear at Day break this Morning that the Gentlemen and Malitia of Lancaster County might take such steps as they think most Prudent. I though it Propper to acquaint you with a piece of intelligence that I have Received by old Ogaghradariha, one of the Six Nations Chiefs, who came here yesterday in the afternoon, and is as follows, that bout 10 Days before he left Tioga [on the New York border] there was two Delaweare Indians arrived there who was just come from Fort De Quesne [Pittsburgh] & informed him that before they left said Fort there was one thousand Indians Assembled there who were immediately to march in conjunction with a Body of French to Attack this fort, (meand) Fort Augusta, and he, Ogaghiadariha, hurried down here to Give us the information. He says further, that the day before he came in here he Saw upon the North Branch [of the Susquehanna River] a large body of Delaware Indians & Spoke with them, & they told him there were going to speak with ye Governr of Pennsylvania, whatever intention they have they are marching towards our inhabitants.

I am, Sr,

Your most obedient

Humble Servt,

David Jameson

Various surviving letters and accounts show that Jameson’s duties took him to various frontier stockades. In a letter from Paxton (near modern Harrisburg) dated 10 January 1758 Jameson reported that heavy snow had prevented him from sending bateaux (boats) up the Susquehanna River with supplies. In May 1759 he submitted accounts for recruiting at York; on 11th December 1759 he wrote from Fort Pitt about the condition of the garrison there and the lack of essential supplies, and again on the 18th about the numbers in the garrison, and on the 29th from Fort Ligonier about Virginia troops taking over duties there. In October 1760 he was again at Pittsburgh

In June of 1758 he was at York and wrote from there to Governor Denny at Philadelphia about his difficulties in recruiting:

York Town, ye 6th June, 1758

Sir,

Agreeable to the Orders I received from Coll. Bouquet, I arrived in this Town last Saturday; I yesterday examined and passed [forty-]four of Captt. Hunter’s Recruits, there is more of them to be in Town this day, than will compleat this Company; Captain McPhearson’s Company, he informs me, is full; Capt. Hamilton & Capt. M’Grew’s Company’s, I am informed, is not yet near full; The recruits are so scattered throughout the Country, that I believe it will be the latter end of the Week before they will all arive in Town. I find it extremely difficult to keep the recruits in order, for want of Sergeants that understand duty, & have not so much as a single Drum; None of the Recruits are furnished with Cloathing, or any necessaries for marching.

I was desired by Coll. Boquet to try if possible, to get the Recruits to find their own Arms, but I find this impracticable; of the 44 that passed yesterday, not one-third of them had arms, or could be prevailed on to get them, therefore I shall find it extremely difficult to get as many arms as is necessary for the men that are to escort the Waggons this Week to Fort Loudon; of this I have informed Coll. Bouquet by a letter this morning.

I am, Sir,

Your most obedient and most

Humble Servt,

DAVID JAMESON

Later that year Dr. Jameson was present at the Battle of Kittanning on 8th September, which marked a turning point in the War on the frontier, for it was the first major colonial success against Indian raiders. According to the famed Dr. Benjamin Rush, David Jameson was then acting “as Surgeon of his regiment, and dressed the wound of General Armstrong, received in that battle.”

At the end of the War, Dr. Jameson returned to civilian medicine and civic life at York. Only a few years later, however, he was again called to serve in the Pennsylvania militia. When the decisive break between Britain and the Thirteen Colonies was approaching, Dr. Jameson was an early and vocal advocate of separation from the mother country. He was said to have “despoiled his fair estate near York of acres of its fine woodland, in order to contribute, without money and without price, to the aid of ‘the Grand Cause’.”

Though above the age of sixty, he again took an active military role in the early years of the Revolutionary War, with the rank of Colonel. His grandson, John Barr, Esq., stated that David Jameson

served under General Washington in the battles of Princeton and Monmouth, where he was wounded.

The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton by John Trumbull, Dr. Benjamin Rush and General George Washington enter from the background, with Captain William Leslie, shown on the right, mortally wounded.

The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton by John Trumbull, Dr. Benjamin Rush and General George Washington enter from the background, with Captain William Leslie, shown on the right, mortally wounded.

He was a part of the time a Surgeon in the Revolutionary War, and a very skillful one; and also spent much of his money to get necessary stores and medicines for the sick and wounded: for which neither he nor his descendants ever received any compensation.

In 1776, when the British threatened New York, Jameson was in the First Battalion of Pennsylvania militia that marched to help Washington; during the latter part of that year he was surgeon to the First Regiment of the Flying Camp headquartered at Perth Amboy, New Jersey. After the reorganization of the state militia, in 1777, he commanded the Third Battalion. On November 24th of that year, at Camp White Marsh near Valley Forge, Jameson reported that he had 3 companies, 3 captains, 4 lieutenants, 3 ensigns, 1 adjutant, 1 quartermaster, 9 sergeants, and 70 men fit for duty out of a total of 165. The Pennsylvania Militia at this time were part of Washington’s army which was warily watching the British army occupying Philadelphia. Unable to attack the fortified city, Washington waited until General Howe’s army ventured out of the city at midnight, 4th December, in an attempt at a surprise attack. Washington’s army was awake and ready, however.

Johann Martin Will. View from the British Positions at the Battle of White Marsh, 1777. Washington’s right flank is at the left in the distance. Library of Congress.

The American forces met the Redcoats at White Marsh. The Pennsylvania militia on Washington’s right flank (at left in the engraving) were ordered to support Morgan’s riflemen in an advance. The militia had a short, fierce skirmish against Howe’s forces in which the militia commander, General William Irvine, was captured, but no tactical advantage was gained by either army. After maneuvering for three days, Howe returned to the comforts of Philadelphia for the winter. After that time, Jameson’s regiment was mainly occupied guarding British and Hessian prisoners at York and Lancaster. Jameson seems to have been called on primarily to function as surgeon for wounded soldiers.

C. Dr. Jameson in Civic Life

Along with his officering in two wars, David Jameson was also an active political and civic leader in the county seat of York. He was appointed Justice of the Peace in 1764 and also Judge of the Court of Quarter Session and Common Pleas, in which positions he continued to be reappointed up through 1777. He served also as a special Commissioner to hear cases involving Negroes; he was the medical officer for the York Gaol; and he was consulted about matters as varied as the boundaries of Indian lands and the plight of prisoners in the lockup. In 1779 he was one of two J.P.s instructed by the Governor’s Council to look into alleged misappropriation of public stores at York; their investigation resulted in a flurry of letters and depositions and led to the suspension of the Commissary, a Continental officer named John McCallister. The citizenry of York were outraged by stories of the Commissary’s graft, such as diluting precious whiskey with water and feeding his hogs “flour and good biscuit” when American soldiers were on short rations. There was an ongoing hullabaloo in the town which made Jameson’s investigation harried and downright dangerous.

With all this public life, Jameson also found time to pursue interests in physiology, surgery, and the sciences generally. He became a corresponding member of the American Society, which merged into the American Philosophical Society, where a number of his letters are preserved, as well as his report of meteorological observations in 1772.

At some point during or after the War, Dr. Jameson and his family left York and moved westward to Shippensburg, PA. The date of this move is uncertain; several of Dr. Jameson’s children were thought to have been born there rather than at York, including Rachel in 1777 (though her father was assessed taxes in York in 1778 and 1779). He was certainly living there in 1796 when he is styled in a deed “David Jameson of Shippensburgh . . . Practitioner in Physick.” He died by February 1800, probably at Shippensburg; his estate was probated, however, at York.

D. David Jameson’s Family

It is possible, though no record has turned up, that Jameson had been married when a young man and that his eldest son, Robert, was a product of that marriage. Robert as a young adult left Pennsylvania for South Carolina, perhaps the home of his mother’s kin. In any case, at the age of nearly 50, in about 1766, Dr. David Jameson married Elizabeth Davis, daughter of Thomas Davis of York, PA. A descendant, Cassandra Jameson Gibson, recalled what she had heard about the couple’s relationship:

I have never heard anything of our [grandfather] as to his personal character, except that he was a student so completely absorbed and indifferent to pecuniary affairs that but for the energy of his wife, his family would have been without the necessary wherewithal. He, I believe, never thought of his bills at all, and they were always collected by his wife.

Elizabeth was much younger than her husband, but both were hale and vigorous: he fathered a dozen children—the last child born when the good doctor must have been over 70—and his wife Elizabeth bore at least eleven children over a span of more than thirty years.

The administration of the estate of Doctor David Jameson was granted to his widow, executrix, on 17th February 1800 at York. Later the widow Elizabeth remarried twice, first in about June 1807 to Colonel George Irwin, of York. After his death she moved to Columbus, Ohio, and there on 19 April 1815 she married Colonel Robert Culbertson, with whom she was already connected by marriage of their children. She died and was buried at Columbus before 14 March 1820; she had outlived her third husband, who died shortly before her.

Children of David Jameson were:

i. Robert Jameson, born ca. 1767. He “went South” and settled in South Carolina.

ii. Ann Jameson, born 1768, died 1838; married (1) in 1788, James Crawford, who died in 1812, and (2) ____ Perry

iii. David Jameson, born in York, became a physician and practiced at Shippensburg, then before 3 May 1803 moved to Franklinton (now Columbus), Ohio, where he became one of the Associate Justices of the first court in Franklin County. He married in Pennsylvania Sarah Culbertson, daughter of Colonel Robert Culbertson (his mother’s third husband). David and Sarah had seven children. He died about 1823, when at least one daughter was married and his sons were of age. Sarah died in 1824.

iv. James Jameson, born 1771. For his life, see Chapter 2.

v. Thomas Jameson was born and resided in York; he studied medicine with his father and set up his practice at York. He had his residence and office right in the center of York, in a building at the southwest corner of Centre Square. He owned also and resided for some years on a farm in Paradise Township outside York. He was a physician to the County Poor House beginning 1804, in which capacity he regularly called his famed surgeon brother Horatio as consultant in difficult cases. Thomas served also as coroner 1808-1812, and served as sheriff for three years beginning 1821. He married Catharine Hahn, of York, and had four children: Thomas, Catharine, Charlotte and Margaret. After 1815 he married a second time to a widow Sarah McClellan, and had a son Charles by her ca. 1823. He bought and sold numerous tracts of land in York County. He died in 1838 while visiting his brother in Baltimore, Dr. Horatio Gates Jameson.

Dr. Thomas Jameson was a great fan of the sport of cock-fighting, and he developed a stock of game fowl known as the “Jameson breed.” Glossbrenner’s History of York County records that “on the night of the 7th of March 1803 they [some African Americans] set fire to the stable of Mr. Edie . . .‘ The flames were commun-icated with uncontrollable rapidity to the stable of Dr. Jameson on the west and to that of the widow Updegraff on the east”—and all those buildings were destroyed. An aged resident of York many years later recalled of that night, “The Doctor was a great sportsman, and had a fine hound and some game chickens in his stables, with his horse and cow. Not being able to save all he took out the hound and chickens and left the horse and cow to burn.”

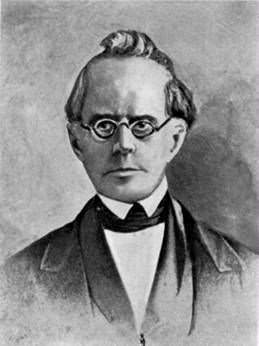

vi. Horatio Gates Jameson was born at York in 1778, studied medicine under his father and received a medical degree from the University of Maryland in 1813. He lived at various times in Somerset, Wheeling (now WV), Adamstown, and Gettysburg. In about 1810 he moved to Baltimore, where he established a large practice. He gained a wide reputation for his success in the cholera epidemic of 1832 in Baltimore and Philadelphia. He published Lectures on Fevers (1817), American Domestick Medicine (1817—this book was a standard home medical text for a generation), and Treatise on Epidemic Cholera (1855; this book is available online through Google books), and he was editor of the Maryland Medical Recorder 1829-1833. He traveled to Europe in 1830  Horatio Gates Jameson and toured the Continent, consulting with eminent physicians and gaining a lofty reputation. He founded Washington Medical College in Baltimore and served as its first president; he also accepted a post as president of the Ohio Medical College in Cincinnati, but after only a year his wife’s illness forced him to return to Baltimore. In the last year of his life he left Baltimore and returned to York, his birthplace, hoping to recover his ancestral homestead (he was unsuccessful). He died in July 1855 while on a visit to New York City. He married 3 August 1797 Catharine Schevell of Somerset, PA, where he then resided, and they had children: Cassandra, Elizabeth, Rush, Catharine, Alexander Cobean, David Davis, Horatio Gates, Iphis and Catharine (the last two died in infancy). His first wife died 2 November 1837, and in 1842 he married widow Hannah J. D. (Fearson) Ely of Baltimore, who survived him by nearly thirty years.

Horatio Gates Jameson and toured the Continent, consulting with eminent physicians and gaining a lofty reputation. He founded Washington Medical College in Baltimore and served as its first president; he also accepted a post as president of the Ohio Medical College in Cincinnati, but after only a year his wife’s illness forced him to return to Baltimore. In the last year of his life he left Baltimore and returned to York, his birthplace, hoping to recover his ancestral homestead (he was unsuccessful). He died in July 1855 while on a visit to New York City. He married 3 August 1797 Catharine Schevell of Somerset, PA, where he then resided, and they had children: Cassandra, Elizabeth, Rush, Catharine, Alexander Cobean, David Davis, Horatio Gates, Iphis and Catharine (the last two died in infancy). His first wife died 2 November 1837, and in 1842 he married widow Hannah J. D. (Fearson) Ely of Baltimore, who survived him by nearly thirty years.

vii. Cassandra Jameson was born in Pennsylvania and married ____ Culbertson, Esq., a hatter of Zanesville, Muskingum County, Ohio; he was a distant relative of the Culbertson husbands of her sister Emily and her mother Elizabeth. The couple lived and died in Zanesville, where they had several children: James, Jameson, Perry, Jane, Emily, and ____.

viii. Henrietta Jameson was born in Pennsylvania and moved to Franklinton, OH (later incorporated into Columbus); there she married 1 February 1804 Arthur O’Harra, a farmer and dealer; his farm was near the later Greenlawn Cemetery of Columbus and adjoined the farms of Henrietta’s brother David Jameson and of her step-father Col. Robert Culbertson. They had five children: Jefferson, Irwin, Horatio Gates Jameson [named after his famous surgeon uncle], Louisa, and Elizabeth.

ix. Emily Jameson was born at York; she married James Culbertson, son of Colonel Robert Culbertson, her mother’s third husband, moved with him to Ohio, and had several children. Emily was remembered in the family as a great beauty, who “combined with her beauty of form and feature, wonderful physical grace and activity.” The Memoir editor tells a story (p. 41n.) from before her marriage to Culbertson: she was engaged to a man from Maryland’s Eastern Shore, but on the wedding day waited in vain for him to appear for the ceremony; she was so mortified that when he arrived the next day and explained that he had been prevented by a storm from crossing Chesapeake Bay, she refused him and he went away sorrowful.

x. Rachel Jameson was born in 1777 in York or Shippensburg, Pennsylvania; she moved to Franklinton, Ohio, somewhat later than her siblings, and there married on 26 March 1814 Samuel Barr, a merchant. They had six children: Keys Jameson, John, Henrietta, Elizabeth, William McCune, and Samuel (the last two died in infancy). Rachel died in July 1824; her husband remarried and died 21 March 1853.

xi. Joseph Jameson, born in Pennsylvania, became a physician and practiced at Franklinton, Ohio before 1803, and later in Columbus. He married Lydia Stewart of York and had several children born in Franklinton: David, Joseph, Jane, Mary, and a son. Joseph lived for a time on Front Street in Columbus, near the Scioto River.

xii. Amelia Jameson, baptized 18 Nov. 1800 at St. John’s Episcopal in York; probably died in infancy.

NOTES FOR CHAPTER 1

Along with the Memoir of David Jameson, Esq., M.D. (hereafter cited as Memoir), other basic sources for David Jameson’s life include: George R. Prowell, History of York County Pennsylvania, 2 vols. and Index (Chicago: J. H. Beers & Co., 1907), esp. 518-19; Whitfield J. Bell, Jr., Patriot-Improvers, vol. 2 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1997); and numerous letters to and from Jameson in various collections, particularly the Pennsylvania Archives (Harrisburg) and the library of the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia). No portrait of David Jameson is known to survive.

Memoir, 34. The editor of the Memoir, a great-grandson of David Jameson, speculates (34n.) that his forebear may have been related to Professor Robert Jameson (1774-1854), the famed geologist and professor of natural history at the University of Edinburgh. There may be no more to this suggestion than to his introducing of a possible family link by marriage to the noted author Mrs. Anna Jameson (who was born in Ireland).

Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 3, 21:6, 170, 330, 476, 647. [Pennsylvania Archives is a multi-volume work in nine series which reprints documents preserved in the state archives at Harrisburg.]

Memoir, 3; York County Archives, Deeds, 2L, 397 and 2P, 309; see Neal O. Hively, York County, Pennsylvania Original Land Records, vol. 9 York, Windsor and Lower Windsor Townships, 52-3; the estate straddled the border of modern York and Spring Garden Townships.

Henry J. Young, Notes and Documents Concerning the Manorial History of the Town of York (York: South Central Pennsylvania Genealogical Society, 1992), 28; Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 1, 4:335 and Ser. 3, 26:451; David Jameson to Captain Evan Shelby [on printed form], 24 June 1767, copy in Jameson file at York Historical Trust Library from a copy at The New-York Historical Society.

Pennsylvania Archives, RG-17, Patents AA-14-568/9/70 (26 July 1774) and Copied Surveys A-71-261/2/3; a David Jameson (possibly a different man) was issued a warrant in 1773 to survey 300 acres on Nescopeck Creek in then-Northumberland County, but the warrant was released before the survey (Warrant Register, Northumberland County, p. 138 item J-32).

Thomas Balch, Letters and Papers Relating Chiefly to the Provincial History of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Crissy & Markley, 1855), 64-66. For description of the troubles of Colonel Clapham, including a mutiny, see J. F. Meginness, Otzinachson; or, A History of the West Branch Valley of the Susquehanna (Philadelphia: Henry B. Ashmead, 1857), 75-98.

Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 5, 1:62, 1:298, 1:311. Fort Augusta, built in 1756 near the sizeable Indian town of Shamokin (now Sunbury, PA), was the most important British fortification along the Susquehanna River. Fort Ligonier (Ligonier, PA) was established in 1758 as a staging area, about 50 miles east of Pittsburgh, for a British attack on France’s Fort Duquesne. Fort Duquesne, at the junction of the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers, was built by the French in 1754; the British Forbes Expedition seized the site in November, 1758, and built a larger fort which they named Fort Pitt. Fort Halifax was along the Susquehanna River about fifteen miles north of Harrisburg; it was used only from 1756 to 1757.

American Philosophical Society Library, Manuscripts, Online Guide at http://www.picosearch.com/cgl-bin/ts.pl, accessed 10 December 2007, items in the Burd-Shippen Papers 1708-1792,

Pennsylvania Archives, Colonial Series, 7:529-30, 7:652-3, 9:201, 9:543, l:731, 10:163; Ser. 2, 3:116, 12:27, 12:201; Prowell,, History of York County (see Note 1), 225.

APS Library, Manuscripts, Online Guide (see note 14), Manuscript Communications 1756-1837, and Edward Shippen Papers 1727-1789.

Memoir, 34; she identifies Dr. James Jameson as “our great-grand-father,” but she was his granddaughter through his son Horatio Gates Jameson; perhaps the editor’s informant was not Cassandra but one of her children.

The editor of the Memoir, Horatio Gates Gibson, argues (p. 35n.) plausibly for an earlier marriage: it seems unlikely that the doctor would wait until age 45 or older to first marry; his eldest son went to live in South Carolina (suggesting possibly that his mother’s kin were there) and Elizabeth seems to have lost contact with him, a contrast to the fact that when she moved to Columbus, Ohio all but four of David Jameson’s other children went with her or followed her, and she kept in touch with those four. Mr. Gibson goes on (p. 36n.) to a perhaps far-fetched speculation that Robert Jameson may have been the grandfather of Confederate notable General David Flavel Jameson, who presided over the Convention of South Carolina which voted to secede from the Union in December, 1860.

York County Register of Wills, Administration Bonds, 2A, 276, and Accounts, 30 Apr. 1802; Marriage Records of First Presbyterian Church of York.

Except as otherwise noted, information on the children is from the genealogy in the lengthy APPENDIX to the Memoir prepared by the volume’s editor, Horatio Gates Gibson.

Memoir, ; York County Deeds 2Q:211 (1803), 2S:41 (1805), 2S:43 (1805), 2T:185 (1800), 2T:187 (1802), 2X:25 (1811), 3L:427 (1824), etc.

History of Cumberland and Adams Counties, Pennsylvania (Chicago: Warner, Beers, 1886), 499-500; website “Medicine in Maryland 1752-1920” (http://mdhistoryonline.net/mdmedicine/cfm/dsp_detail.cfm?id=1395), accessed 12 December 2007; the portrait is from that site, reproduced there from Eugene F. Cordell, The Medical Annals of Maryland 1799-1899 (Baltimore, 1903), f. 750. The Gothic Revival house that Horatio built in 1857 in Mt. Washington, Baltimore County, is on the National Register; see a photo and description at website http://marylandhistoricaltrust.net/nr/NRDetail.aspx?HDID=636

Chapter 2

DR. JAMES JAMESON OF ALLENTOWN

Dr. James Jameson was born in 1771 and died in 1831. He had a successful medical practice in Allentown, PA (then named Northampton). Though we know relatively little of his career as a physician, we do know that he was well-known and well-regarded in the town. He was best known as the leading mover in the building of the first bridge across the Lehigh River at Allentown.

According to Matthew Henry’s History of the Lehigh Valley (1860), a ferry was established across the Lehigh River at Allentown as early as 1754 and continued in service until the building of the bridge in 1812. An effort had been made in 1797 to erect a bridge and an act of incorporation passed the legislature that year, but the project failed for lack of funds. Henry wrote that

it is doubtful whether the bridge would have been erected in 1812 if it had not been through the exertions of James Jameson, an enterprising citizen of Allentown. The old charter having expired, a new one was granted [by Act of the legislature] on the 2d of March, 1812. A chain bridge was then erected at a cost of $15,000, which stood until April 13, 1828, when it was set on fire and burnt down. Another bridge which was subsequently erected was swept away by the high freshet of January 8, 1841.

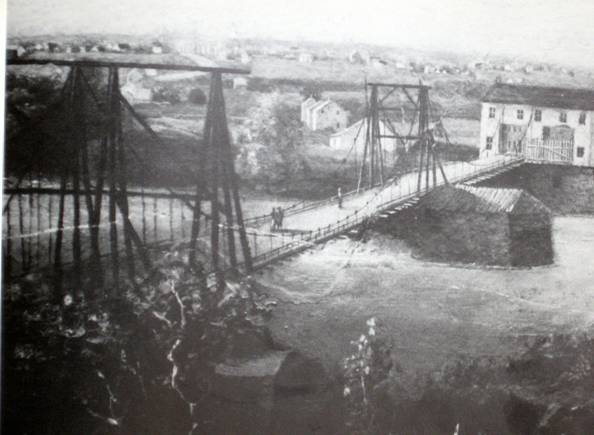

Jameson’s bridge company used a then-new and daring technology, the chain suspension bridge. American entrepreneur James Finley had built the first such bridge, a 70-foot span, at Greensburg, Pennsylvania in 1801 to a design which he patented in 1808. The Finley-style Allentown structure consisted of two whole and two half span lengths for a total length of 475 feet. It was the first multi-span suspension bridge ever built. It was a dual-carriageway bridge with four chains, two for each road, suspended from wooden structures erected on three large stone piers in the river. Two of these supports were wooden towers, while the third, on the Northampton shore, was a large building (see photo, p. 18).

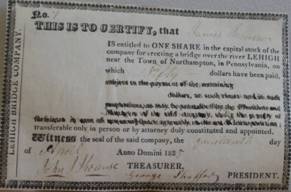

The bridge company was capitalized at $15,000, selling 159 shares; the largest shareholder was Dr. James Jameson. By 1828 he had acquired almost all the shares and was considered the “sole proprietor.” The company was reorganized in 1835 and 300 shares were issued at $50 each; these stock certificates still survive (now at the Lehigh County Historical Society Library), and almost all of them were issued to “James Jameson,” as was No. 7 shown here (reduced about 30%).

The building on a pier in the river near the Northampton end of the bridge had two large openings for access to the bridge’s two roadways. This building became Dr. Jameson’s residence, where he could keep an eye on traffic, toll-taking, and safety. On the pier in the middle of the river he built a stable beside the roadway, and that structure, unfortunately, caught fire one night, an event which caused a local sensation. On 20 March 1828 The Lehigh Herald reported:

FIRE! Lehigh Bridge Burnt!

On Thursday night last, the citizens of this place were awakened from their slumber, about midnight by the apalling cry of fire. The different fire companies repaired with laudable alacrity to the engines and the citizens generally hastened to the spot, but found that they could render no assistance, as the frame building on the middle pier of the Lehigh Bridge over the Lehigh River occupied as a stable by the proprietor, Dr. James Jamison, was inveloped in flames and the planks, rafters, uprights and other wood near that pier, were burning — In a very short time, this was burnt through and the whole of the bridge [i.e., one of the two roadways] between the middle and the other piers, fell with a tremendous crash into the river, and thus stopped the further progress of the devouring element. The buildings on the other piers received no material damage. What rendered this conflagration particularly affecting was the burning up of two horses and a fine cow. The poor animals were seen struggling in the flames — but no assistance could be rendered and they were burnt to death. It is not ascertained how the fire originated — but many believe it to be the work of an Incendiary. A great number of the planks and other lumber as well as the chains may be used again in the rebuilding and the loss is therefore not as heavy as it would have been if the bridge had not broke down — it may be estimated a loss of 3,000 dollars. Although a public loss, yet Doctor James Jamison suffers most, being sole proprietor. We are happy to add that measures have already been taken by this enterprising gentleman to rebuild the bridge without delay.

.

In the event, though, the fallen span was never rebuilt; the single surviving roadway apparently served adequately for the traffic. The photograph is of a painting by an unknown artist made about 1830, showing the bridge after the 1828 fire (the painting is now at the Lehigh County Historical Society, Allentown). The town of Northampton is seen in the distance to the west. The artist clearly shows the double support frame on the pier in the foreground, but only one roadway. The tollhouse (Dr. Jameson’s residence) on the opposite shore has two large openings, but the right-hand one is blocked by a fence. After thirty years of service, this bridge was swept away in a flood in 1841.

Dr. Jameson was also an investor in other bridge projects, notably the Lehigh Water Gap Bridge, also a Finley chain bridge, which was completed and chartered by the Governor on 16 June 1826. This bridge a few miles north of Allentown was the longest operating iron chain bridge ever constructed. It survived the 1841 flood and others, and continued in use, incredibly, for 107 years, until 1933. At the time of chartering, Dr. Jameson held 24 of the 159 shares of stock in the corporation, more than any other shareholder. He invested also in the Berwick Bridge and in the Reading and Perkiomen Turnpike.

Dr. Jameson wrote and signed his will on 19 March 1831; just two days later, he died at his house on the Lehigh Bridge “from a sudden consumption [?] . . . in age around 57 years.” His son James Jr. erected a monument in Old Allentown Cemetery which reads:

TO THE MEMORY

OF

Dr. James Jamison,

Who was born A.D., 1771, in York County, Pa, and departed this life, March 19, 1831, aged 60 years.

His will directed that his goods all be sold; he bequeathed varied amounts to three children (James Junior, $5,000; David, $1,000; and married daughter Nancy Myers, $2,000) and directed that any remaining amount be split evenly among the three children. The daughter’s husband, Henry Myers, challenged the will, but on what grounds is not known. The detailed estate inventory indicates a comfortable but not lavish household; among the more valuable items listed are a Bay Horse at $50, and one “Black or rather Brown Horse,” $40. The inventory listed ten bad debts (“Desperate”) owed to the doctor, some as old as 1809. The great bulk of the estate valuation was in 264 shares of stock of the “Company for erecting a Bridge over the River Lehigh near the Town of Northampton,” valued at $6600.

Dr. Jameson was married about 1800 to Elizabeth Myers, daughter of David and Anna Sultzbach Myers of East Berlin, Adams County; she was born 26 May 1780 and died 14 (or 10) October 1805, age 25, with burial at Abbottstown, Adams County. Her father (b. 1749) was son of immigrants Nicholas and Anna Margaretha Albert Myers; Nicholas was born in Hamburg, Germany, immigrated to America in 1744 on the ship Aurora, and died 1787 at Kingston, PA. His ancestry is probably in the line of these men born at Thal Lichtenberg, Kusel, Germany: Johannes “Hans” Meyer (b. ca. 1605) married to Catherina ____; Hans Hermann Meyer (b. ca. 1634) married to Barbara Schramm; and Hans Hermann Meyer (1669-1729) married to Elisabetha Catherina ____.

James and Elizabeth Myers Jameson had two children:

i. Nancy Jameson, who married her first cousin Henry Myers, son of Jacob Myers of New Chester, PA; they had children Jacob A., Singleton, Henry Jameson, Ann Elizabeth Johnston, Horatio Gates, David P., William.

ii. David Jameson; he had a farm 1½ miles east of Gettysburg; his brick barn, the largest in the county, was used as a field hospital by the Confederates during and after the battle. He married and had children Henry M., Amelia, Nancy, James B., Rush, and Elnora.

After his wife’s death, Dr. Jameson apparently had an extended liaison with a much younger woman, Catharina Siegfried. She was the daughter of Andreas and Anna Elizabeth (Hertzog) Siegfried of a pioneer farming family in Whitehall Township just north of Allentown. The first Siegfried in the township kept a ferry across the Lehigh River and developed a settlement that was called Siegfried’s Dale. Catharina was born 26 January and baptized 8 April 1786 at Egypt Reformed Church a few miles north of Allentown. She bore Dr. Jameson two children whose records of birth and baptism are translated below from the German-language records of Egypt Reformed Church:

______________________________________________________________________________

Parents Child Sponsors

James Jameson Jacobus Solomon Siegfried

Catharina Siegfried b. Nov. 7, 1808 single

bp. Dec. 11, 1808

James Jameson Daniel Susanna, wife of

Catharina Siegfried b. Dec. 17, 1812 Peter Siegfried

Bp. Feb. 15, 1813

______________________________________________________________________________

Catharina Siegfried about 1817 married local farmer John Roth, Jr. (born 7 November 1787, died 28 February 1826) and had at least five children with him. It isn’t apparent why she never married the father of her first two children.

Since the name “Jacobus” is the Latin form of “James,” the first of Catharina’s two sons is evidently the person designated in Dr. Jameson’s will as “James Jameson Junior of the Borough of Northampton [Allentown] in said County of Lehigh, Taylor.”

It is curious that Dr. Jameson’s will bequeaths a large sum to this elder of his sons by Catharina, but doesn’t even mention the younger son, Daniel. At least one family historian concluded that Daniel Jameson must have died young, but there is good evidence that in fact he lived a full life, dying at age 87 in 1900 (see Chapter 3). We simply don’t know why Daniel was omitted from his father’s will, nor is there any clear indication whether one or both sons ever lived in their father’s household. Another curiosity: by the time of the 1850 census tailor James Jameson was living in the North East Ward of Reading, PA, just two miles or so from Daniel’s earlier residence (ca. 1836-1839) at the village of Port Carbon. We might guess that James first became acquainted with the Reading area while visiting his brother’s young family, but no record survives.

Daniel’s brother James Jameson Jr. became a tailor and then a clothing merchant, at first in his native city of Allentown. In the 1840 U.S. census he is listed there with a large household of six males and five females, several of whom were over age fifteen and were probably workers in his shop.

In about 1844 James Jameson Jr. moved about twenty miles away to Reading, where he became a successful merchant, a civic leader, and an elder in the Presbyterian Church. On 21 September 1832 he married Mary Worman (born ca. 1812) of Allentown, and they had these children (with approximate birth years):

Ellen 1834

Maria 1836

Albert 1838

Anna 1840

Mary 1842

Sarah 1845

Edward 1847

(Infant) 1849

In the 1870 census, Reading North East Ward, James’ real estate was valued at $86,000 and personal estate $14,000, figures ranking him among the wealthy elite of the city.

We learn a lot about James Jr.’s character from an obituary reprinted by the editor of the Memoir (page 43n., source not cited):

ELDER JAMES JAMESON

Mr. James Jameson, of Reading, died in that city, January 25, of Pneumonia.

He was born in Lehigh County eighty-two years ago, and for twelve years was in the mercantile business in Allentown. In 1844 he removed to Reading, where he resided until his death. He was one of the corporators of the Presbyterian Church at Allentown, being one of its first elders and superintendents of the Sunday school. He continued to serve the church at Reading as elder and was deeply interested in her prosperity, giving freely of his time, labor and money. He was treasurer of the Reading Relief Society, of the Soup House for the destitute, and contributed largely to the establishment of the Reading Hospital and Lincoln University. His innumerable acts of charity and deep interest manifested in all benevolent operations are well known. It is eminently true of him that there was something finer in the man than anything he said or did. His natural probity, candor and quiet spirit of honor commanded the respect and confidence of all who knew him—or felt the power of his presence. But over and above all these shining qualities of his character he was most conspicuous as a Christian. . . . His remarkable faith upheld him in the day of trial, gave him patience during his distressing illness, and supported him when death was near.

Matthew Henry, History of the Lehigh Valley (Easton: Bixler & Corwin, 1860), 278; documents about the chartering of the bridge are in Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 9, 1:348, 4:3164-66.

Death notice in a German-language Allentown newspaper, Der Friedens Bothe, 24 March 1831; monument inscription: Memoir of David Jameson, Esq. M.D. (see Chap. 1 note 1 above), 42.

Memoir, 35-36, 57-58; online “Myers DNA Project” ( www.worldfamilies.net/surnames/m/myers/pats.html ), accessed 6 Dec. 2007.

T![]()

The Jameson Family

Anchorage, Alaska

Telephone: (907) 274-9954

© 2007 Alaska Internet Marketing, Inc

This Site Maintained by Alaska Internet Marketing, Inc.